(Originally published in Atlantis Rising #33 – May/June, 2002)

My “Mystery of Bannockburn” article, published in Atlantis Rising issue 31, proposed that the great 1314 battle for Scottish independence had been stage-managed by a clandestine brotherhood that stood on both sides of the battleline, and had been forever fixed in time as an event of great symbolic significance by uncannily mirroring a simultaneous encounter in the heavens above.

Bannockburn, I proposed, was an epic contract between enemies of convenience, written in the invisible ink of the stars at daytime, and sealed with the blood of battle. It follows that many of the rank-and-file who fought that day thought they were fighting only for Freedom, but in fact were also fighting so that certain “forbidden” truths could be sent quietly forward to a more-enlightened time. The brotherhood knew that books could be burned, and messages carved in stone could be crushed into dust, but the arrangement of the heavens would forever remain safe from tampering. And so it was there, supported by some pointed hints in the “official” record, that they hid their secrets!

500 years after the Battle of Bannockburn, that brotherhood would meet again to fix yet another date in time and to reaffirm their ancient contract. Once again they would pretend to be enemies, and once again they would hide their secrets in the sky.

Let’s go back.

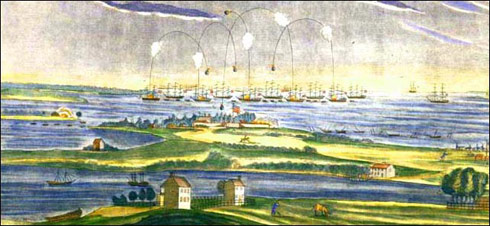

Very early on the morning of September 14, 1814, a young American lawyer named Francis Scott Key stood on the deck of a British “truce” ship, waiting for the dawn. In a letter to a friend, Key would later describe dawn’s arrival as a “bright streak of gold mingled with crimson shot athwart the eastern sky, followed by another and still another, as the morning sun rose in the fullness of his glory, lifting ‘the mists of the deep,’ crowning a ‘Heaven-blest land’ with a new victory and grandeur.”

He had just witnessed the end of the 25-hour naval bombardment of Maryland’s Fort McHenry, the fort that guarded the entrance to Baltimore harbor.

The sight of an immense American flag, flying “o’er the ramparts” of the fort, would inspire him to scribble down the lyrics to “The Star-Spangled Banner.” That anthem would be Key’s single claim to fame, and would commemorate the most-memorable event in America’s otherwise most-forgotten war.

Often referred to as America’s second war of independence, there were several reasons for the War of 1812, but the immediate reason was the British navy’s nasty habit of boarding American ships and “pressing” certain of the crew into its own ranks on the grounds that they were British deserters. The action rankled, and America went to war for the first time as a sovereign nation.

Often referred to as America’s second war of independence, there were several reasons for the War of 1812, but the immediate reason was the British navy’s nasty habit of boarding American ships and “pressing” certain of the crew into its own ranks on the grounds that they were British deserters. The action rankled, and America went to war for the first time as a sovereign nation.

Much has been speculated about the early foundations of America. It has been proposed that the country was begun as a grand experiment of the brotherhood of Freemasons, a fraternity thought by many to have grown out of the Knights Templar, the mysterious order of warrior monks barbarously suppressed in France on grounds of heresy, among other charges, in 1307. It has also been proposed, however, that many Templars escaped to Scotland, and delivered the decisive blow against the English at Bannockburn. Going underground, the order then cobbled together yet another brotherhood within the civil sector that would survive the Protestant Reformation—the great church schism that gave the Vatican a new force to reckon with. Although the Templar connection is still hotly debated, that new brotherhood is thought to be the Freemasons.

Almost 300 years after Bannockburn, in 1603, the crowns of England and Scotland would finally unite under the first officially Masonic king, Scotland’s James VI.

Shortly thereafter, the great migration to the New World would begin in earnest.

In Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh’s “Temple and the Lodge,” the authors claim that many of America’s founding fathers were Freemasons, and that the precipitating acts of the American Revolution were planned by that brotherhood. Many Freemasons, they claim, were key participants in the famous Boston Tea Party. One of them was Paul Revere—famous for his “midnight ride” to Lexington, where “the shot heard round the world” was fired. It is interesting to note that from George Washington on down there was a disproportionate number of Freemasons among the American high command, including a General Arthur St. Clair, a descendent of Sir William Sinclair who built Scotland’s Rosslyn Chapel, the world’s most revered repository of Freemasonic lore. William, in turn, was a descendent of the man thought to have led the Templar charge at Bannockburn, who was himself ancestor of Prince Henry Sinclair of Orkney, who arguably may have organized a voyage of discovery to the New World in 1398, long before Columbus was a twinkle in his father’s eye.

Baigent and Leigh also imply, however, that the top British commanders were also Freemasons, and showed little zeal to win the war. It was perhaps thought more prudent to let the new land govern itself, while each country’s movers and shakers remained bound by brotherly bonds. A mutually beneficial dialog could then be quietly maintained, while highly motivated hordes of European immigrants proceeded to kick America’s indigenous people about, from place to place, in the great march west.

But they needed a flag to march behind.

It is well known that the first American flag was commissioned by Washington, and was sewn by Betsy Ross. But it is less well known that Betsy’s husband was a brother Freemason, and that Washington described the flag’s circle of stars as “a new constellation.”

While we are taught that the circle symbolizes the 13 original states, could Washington have had something else in mind? Might he have been secretly invoking the Hermetic dictum “As Above, So Below,” a phrase much bandied about whenever Templars, Freemasons, and “underground streams of knowledge” are discussed in the same breath? Could that stellar circle also symbolize the letter “O,” for Orion, the constellation that played such a pivotal role at Bannockburn?

America’s Declaration of Independence, signed by many brother Freemasons, is thought to have been inspired by Scotland’s Declaration of Arbroath, signed shortly after Bannockburn by many names still associated with the survival of Templar and Freemasonic ideals. That stirring document can still be interpreted as a testament to the equality of men and as strong advice to any temporal ruler unwise enough to hold the will of the people in contempt.

During the years following the American Revolution, however, the young nation somehow failed to develop a unity of spirit that the world’s major powers would respect. The war of 1812 would change all that, and the bombardment of Fort McHenry would force the world to see the “Stars and Stripes” with new eyes, and would give the American people a song to sing.

During the years following the American Revolution, however, the young nation somehow failed to develop a unity of spirit that the world’s major powers would respect. The war of 1812 would change all that, and the bombardment of Fort McHenry would force the world to see the “Stars and Stripes” with new eyes, and would give the American people a song to sing.

The British assault on Baltimore was, like the English assault at Bannockburn, a two-pronged affair. British General Robert Ross, who had shown remarkable restraint by burning only the government buildings during his earlier “sack” of the nation’s capitol, led his men towards Baltimore by land. The assault failed when Ross became one of the first casualties and, with an effect eerily reminiscent of a similar event at Bannockburn, his men lost morale.

Meanwhile, the British fleet had anchored broadside to Fort McHenry.

At 7 a.m. on Sept. 13, and continuing for 25 hours with just one several-hour break, British warships bombarded the fort. Key’s lyrics, however, tell us that the bombs were “bursting in air” before reaching their targets. The fuses had been inexplicably set too short to go the distance. But the light of the bombs and “the rockets’ red glare” did manage to give “proof to the night that our flag was still there!”

It was quite a show, and a relatively cheap one. Only four Americans are known to have died during the bombardment.

But there was a much bigger show going on above—one that would outlive the tale we are told today.

At 3:41 a.m., the “morning star” Venus rose above the eastern horizon midway between the forelegs of Leo, just minutes before the rising of Regulus, a significant star in Masonic tradition. If the night had been dark, clear, and eventless, they would have made a pretty pair. But it was raining, the air was full of smoke, and all eyes were trained on the lightshow below.

Mercury rose at 5:16, as Leo stood “rampant” on the horizon in a stance well-reminiscent of the flag carried at Bannockburn—the flag Scots still fly today—followed quickly by the war planet Mars. Even if the bombardment had not been the main focus of attention, these events would have already faded in the light of the approaching dawn.

Just twenty minutes later, giant Jupiter would rise behind the Sun followed shortly by the Moon.

To Earth’s east, if we include the Sun and Moon, six denizens of our solar system lay within just 30 degrees of sky—all but one of those lying within seven degrees—a surprisingly rare alignment.

The planet Pluto surprised me more.

Pluto is the outermost planet in our solar system—so far out that it takes approximately 249 Earth years to orbit the sun. Not “discovered” until 1930, many years after the Siege of Fort McHenry, Pluto takes a very long time to get from one side of the solar system to the other—and yet there it was, due west of the Earth, but part of the same alignment.

But the biggest surprise was the planet Neptune, not “discovered” until 1846, with an orbit time of 165 years. When a line was drawn between Neptune and Pluto, and another drawn between Neptune and the midpoint of Pluto’s easternmost orbit, a compass was formed. When another line connected the two endpoints, a pyramid was formed. And when a line was drawn between Neptune and the Sun, everything weirdly doubled. Astrologers call this particular configuration a “T-square,” and I am told it usually portends events of a sinister nature. But more about astrology later.

As reported, the bombardment had ceased at dusk on Sept. 13, and had resumed at 1 a.m., when the first belt star of Orion broke the horizon. Some 3,000 miles to the East, dawn was breaking in the sky above Bannockburn, and Leo stood defiantly on the Scottish horizon as the bombs again began to “burst in air” above Fort McHenry.

It was a long and noisy night, but the Brits eventually set sail at dawn, leaving the grand finale to the Americans. Meanwhile, in the skies east of Bannockburn, Hercules slew Serpens Aquaticus, the many-headed water serpent. How’s that for synchronicity?

It was a long and noisy night, but the Brits eventually set sail at dawn, leaving the grand finale to the Americans. Meanwhile, in the skies east of Bannockburn, Hercules slew Serpens Aquaticus, the many-headed water serpent. How’s that for synchronicity?

The Battle of Baltimore was fought on many fronts, indeed!

It is a common misconception, not corrected in most history books, that the immense 30×42-foot Fort McHenry flag, presently undergoing restoration in Washington DC’s Smithsonian Institutions, was the flag that was flown throughout the bombardment. It was not.

Fort McHenry commander Major George Armistead had ordered two flags to be made, and had required that one of them should be large enough that “the British would have no trouble seeing it from a distance.” It was the smaller flag that was flown during the bombardment. It was the larger flag, hoisted at dawn, which inspired Key’s song.

Besides the battle damage that could not have happened, what else about the Fort McHenry flag, and the event, might warrant further investigation? Here’s the short list:

- Stitched prominently in red on the third white bar up from the bottom is what has variously been described as a patch, the letter “A” for Armistead, or an inverted “V.” We might ask ourselves the following: Why would someone patch a white bar with a red patch, leave off the crossbar of a letter “A,” or turn a “V” upside down? Might I suggest that this element symbolizes the ever-enigmatic Masonic compass? It is also highly provocative that the letter “B” is almost invisibly embroidered near the top of that compass, perhaps to commemorate Bannockburn.

- Architecturally, Fort McHenry was star-shaped, and had been named after Freemason James McHenry, U.S. Secretary of War during Washington’s presidency.

- There is a legend that, as the British fleet retreated, a rooster crowed defiance from the top of the flagpole. That “herald of dawn” is prominently displayed on the seal of the clan Sinclair, with the motto “Commit thy work to God.”

- The Francis Scott Key Bridge spans the Potomac River from Washington, DC, to Rosslyn, Virginia, perhaps another quiet symbol of the secret transatlantic arrangement made so many years ago.

- The very name “Scott Key” resonates with the suggestion that one key to unlocking this great mystery will be found in Scotland.

While I have described the astronomical arrangement of the skies above Fort McHenry and Bannockburn, and have tipped my hat to the ancient mythological connections, I have paid only brief lip-service to astrological considerations because astrology is not a field I have studied enough to feel comfortable with. Astronomy and astrology were once virtually inseparable disciplines—but not today. While astronomy has acquired a gloss of scientific “respectability,” astrology has not fared so well.

I have nevertheless asked Rab Wilkie and Ed Kohout, both knowledgeable in the understudied field of “Masonic Astrology,” to weigh in with their thoughts on my theories in “100-words-or-less.” Stingy, I know! They have so far weighed in with thousands, and deserve a forum larger than this article can provide to properly present their views in ways that do them justice. I thank them both for helping me adjust the accompanying “Heliocentric View” graphic into something the average reader can visually comprehend. They have also enthusiastically convinced me that what each of us has seen so far is “just the tip of a rather large iceberg.”

I have nevertheless asked Rab Wilkie and Ed Kohout, both knowledgeable in the understudied field of “Masonic Astrology,” to weigh in with their thoughts on my theories in “100-words-or-less.” Stingy, I know! They have so far weighed in with thousands, and deserve a forum larger than this article can provide to properly present their views in ways that do them justice. I thank them both for helping me adjust the accompanying “Heliocentric View” graphic into something the average reader can visually comprehend. They have also enthusiastically convinced me that what each of us has seen so far is “just the tip of a rather large iceberg.”

These are interesting times, indeed!

Some final considerations about the subject at hand:

Consider that the most famous song inspired by the Battle of Bannockburn was “Scots Wha Hae,” written by Scots bard and Freemason Robert Burns. Consider that Freemason Francis Scott Key wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner” during the War of 1812. Consider that Freemason John Philip Sousa’s last performance was to conduct his “Stars & Stripes Forever” in 1932. And finally consider the possibility that a small yet influential clandestine brotherhood may have been marching in secret to its own drum since 1314, if not earlier.

Considering all those things, one might well wonder what Freemason George M. Cohan had in mind when he penned the last few lines of “You’re A Grand Old Flag,” using a phrase from the Robert Burns megahit “Auld Lang Syne.” Could Cohan have written those lines for brothers “with ears to hear?” Italics mine.

Every heart beats true ’neath the Red, White and Blue,

Where there’s never a boast or brag.

But should auld acquaintance be forgot,

Keep your eye on that grand old flag!

Like religion, flags have always had the uncanny ability to keep large groups of people united, ready to fight for any common cause at the drop of a hat. Unfortunately, flags and religion have also been found useful in keeping even larger groups of people apart and, for the most part, that’s why the great Chess game called War has never lacked for pawns.

But who plays the game, and who are the pawns?