(Originally published in Atlantis Rising #48—November/December, 2004—under the title “Return to Rosslyn Chapel”)

France’s Mary of Guise liked a good joke. When England’s King Henry VIII proposed marriage, Mary quipped that her neck was too slender—a cutting reference to the beheading of Henry’s second wife, Anne Boleyn. Mary married Scotland’s James V, instead, and in 1542 gave birth to that nation’s best-known monarch, Mary Queen of Scots, just a week before James died. And in 1546, during her daughter’s minority reign, Mary made a curious “bond” with Sir William St. Clair of Rosslyn.

One passage of that bond has been much debated: “We bind and oblige us to the said Sir William, and shall be a loyal and true mistress to him. His counsel and secret shown to us we shall keep secret, and in all matters give to him the best and truest counsel we can, as we shall be required thereto.”

In 1999’s Rosslyn: Guardians of the Secrets of the Holy Grail the authors say that the “general tone of the letter is bizarre; it is more like that of a subservient person to a superior lord than that of a sovereign to her vassal.”

What secret was Mary shown at Rosslyn that brought about this strange relationship?

Among the many speculations are the Cup of the Last Supper, the mummified head of Christ, the Stone of Destiny, a piece of the True Cross, the Ark of the Covenant, and the genealogical records of a holy bloodline established by a marriage between Mary Magdalene and Jesus. And in a recent issue of Templar History magazine the Grand Herald of the Scottish Knights Templar claims he “once met a chap who was convinced the chapel had been built over an ET-type spacecraft, and presented an excellent case …” The mind boggles.

But while Mary may have been shown any of these things, I believe she was shown something else—something in the architectural fabric of Rosslyn Chapel that was singularly unique to a lineage she shared with William.

Let’s first consider who they were.

Mary was the granddaughter of René II of Anjou and Lorraine, the grandson of René I—a mover and shaker in the heroic career of Joan of Arc. Both Renés inherited the title “King of Jerusalem,” a designation descended from Godfrey of Bouillon’s brother, Baldwin, who first accepted the title. Godfrey had led the First Crusade to liberate the Holy Land from the “infidels.” It was Baldwin who granted the first nine Templar Knights quarters on Solomon’s Temple Mount, beneath which they were to busy themselves digging for a still-mysterious “something” over the next several years. Baldwin also granted the order its first insignia—the equal-and-double-barred Cross of Lorraine. Christopher Columbus acknowledges in his journals that René I granted him his first ship’s command, and it’s thought that Columbus voyaged westward with a cross on his sails. But did that cross have one bar or two? It is perhaps highly significant that René II commissioned the first map that shows the name “America,” dated 1507. That map, recently purchased for $5 million by the US Library of Congress, may ultimately prove to be little more than a spectacularly expensive piece of cartographical propaganda.

William was the grandson of Rosslyn Chapel’s builder, who was himself descended from several other notable St. Clairs: one who married Hugh de Payen, one of the original nine Templars mentioned above; one who was a mover and shaker in the career of great Scots hero Robert the Bruce; and one who may have led a voyage of discovery to the New World in 1398, 94 years before Columbus made the historically approved voyage.

Mary and her vassal clearly had a lot in common before she was shown the “secret” mentioned in her bond. Each of their respective families connects to the creation of a great national hero; each connects to one or more of the original nine Templars; and each in some way connects to the discovery of America.

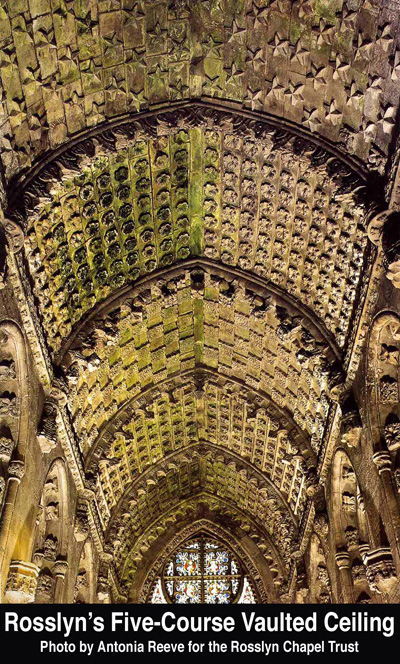

In my “Secrets of Rosslyn Chapel” (Atlantis Rising #38), I talk about recent changes that have been made to the “star course” of Rosslyn’s ceiling, and suggest that the original architectural fabric of the chapel has been tampered with since it was written—not a popular view among Rosslyn’s many “book in stone” fans.

Now I’ll talk about all five courses of the ceiling, and the secret I feel William revealed to Mary when she visited the chapel in 1546, the 100th anniversary of Rosslyn’s foundation.

Let’s follow them inside.

I believe that William would have asked Mary to look up and ponder the chapel’s ceiling, drawing her attention to the fact that while two of the five courses are laid out in true checkerboard fashion with the same number of equally spaced architectural elements, the three remaining courses appear more crowded!

I believe that William would have asked Mary to look up and ponder the chapel’s ceiling, drawing her attention to the fact that while two of the five courses are laid out in true checkerboard fashion with the same number of equally spaced architectural elements, the three remaining courses appear more crowded!

Bearing in mind that the architectural elements of each of those three courses would not only require more carving but would be significantly more difficult to lay out, he would then have asked her why she thought that this were so,

At this point, had Mary’s 16th-century dynastic mind not been moved into sudden revelation, William would have told her what I now tell you.

Rosslyn’s ceiling vault consists of five courses, each made up of its own unique architectural element of floral design, except the star course—what we will call the first course—which consists mainly of stars, laid out like the alternating squares of a checkerboard. The second course is chockablock with architectural elements, containing exactly twice the number of elements as the star course. The third has the same number of elements as the first. The fourth splits the difference between the first and the second and, though there is not as much carving as in the second course, would have been more difficult to lay out, since the easy-to-replicate checkerboard template was not used. The fifth course has less carving than the fourth, but the layout difficulties would have been as great.

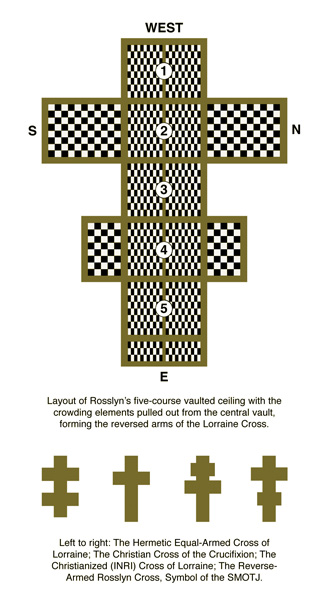

I believe that William directed Mary’s gaze up to Rosslyn’s ceiling, drawing her attention to the overcrowding of certain courses, and then told her that his grandfather, 100 years previously, had hidden a huge Cross of Lorraine in it—with its arms tucked in!

I believe that William directed Mary’s gaze up to Rosslyn’s ceiling, drawing her attention to the overcrowding of certain courses, and then told her that his grandfather, 100 years previously, had hidden a huge Cross of Lorraine in it—with its arms tucked in!

As the accompanying graphic shows, when we move the “crowding” elements away from the ceiling vault, redistributing them according to the harmony of the checkerboard pattern found in the first and third courses, the Lorraine Cross is then revealed with its arms extended. It is not the original equal-armed cross mentioned above, however, but a later incarnation that exhibits a further eccentricity I will cover later.

The symbolism of the Lorraine Cross has been explained in different ways.

Writing in Dagobert’s Revenge magazine, Boyd Rice reports that French poet and essayist Charles Peguy claimed that the double- and equal-armed cross represent “the arms of Christ, the arms of Satan, and, strangely, the blood of both.”

Among other points Rice raises in his article are these: that the cross represents “the union of opposites, the intersection of creative force and destructive force, or the union of male and female principles;” that the bar “above” mirrors the bar “below” and, as such, is symbolic of the Hermetic maxim, “as above, so below;” that the House of Anjou, to which our Mary belonged, advocated “the Royal Art of hermeticism—a tradition which according to legend was passed down to man by a race of fallen angels;” that when the ancient hermetic text Corpus Hermeticum was first published in French, it was dedicated to Mary of Guise; and that Mary “adopted the Lorraine Cross as a personal symbol.”

Joan of Arc historians get irritated when it is suggested that Joan went to the stake clutching the Lorraine Cross to her breast. They point to the “official” documents which record she was given one cross by an English soldier who hastily fashioned it from two pieces of wood, and was given a second by an attending clergyman. But isn’t it possible that the truth of a thing can be secretly hidden in the lie of it? Might not the Lorraine Cross be symbolized by the two crosses the official records say she was given? And since the French Burgundians sold Joan to the English, and the French King she had led to the throne ignored her plight, might we not have here a hidden reference to the expression “doublecross?”

But back to Rosslyn.

It is not the equal-armed cross that William may have shown Mary of Guise, but a later style wherein one crossbar is half the length of the other. At some point, perhaps as a way of bringing an ancient hermetic symbol into the fold of Christian orthodoxy, the upper crossbar was shortened. This crossbar is occasionally referred to as the “INRI” bar, a reference to the inscribed board Pontius Pilate ordered placed above Christ’s head at the crucifixion.

But if we accept that the symbology embedded in the Rosslyn cross indicates that the star course should logically be the “above” part of the cross, and that the extended lower course would be the “below,” then we can see that the crossbars of Rosslyn’s cross have been reversed, with the shorter set below the longer.

Why so?

In my Rosslyn Chapel article I write that one of the Templars arrested on Oct. 13, 1307, and subsequently interrogated, claimed that during his initiation into the order he was shown the single-barred Christian cross, and was told “put not thy faith in this, for it is not old enough.”

In spite of the global controversy now surrounding the not-new theory promoted in Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, which speculates that Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene were married and established a bloodline which has survived down to the present day, might not this short statement by an interrogated Templar indicate that this marriage was just another union along the course of a much older bloodline, and that the original nine Templars had found indisputable proof of it hidden within the Temple Mount?

It would of course have been foolish to hot-foot this heretical proof to the Vatican—especially when there were yet only nine poor Templars in the entire world. Better that the keepers of this new-found knowledge bide their time, consider their options, and develop a viable business plan for the future—which is probably what they did. Over the next two centuries the Knights grew into the richest chivalric order in the world. History tells us that the order was barbarously suppressed in the early 14th century, but many believe its inner circle went underground in Scotland, taking its “truth” with it. I personally believe that the inner circle may have engineered the order’s demise as part of an overall “rightsizing” operation—not a popular theory among the Templars’ sizable fan base.

When William St. Clair and Mary of Guise met at Rosslyn in the chapel’s centenary year, the Church of Rome was in a bit of a tizzy. Catholicism was under siege by a new and troublesome adversary—the Reformation. In one fell swoop, the Christian world was cleft in twain. No longer would Rome be able to raise great armies from its subject nations to crush heresies wherever the Papal finger pointed. There was no longer just one big boy on the block. Another had moved in.

The mightiest church the world had ever known had been “divided” and “conquered.”

But the Reformed Church would not be allowed to remain squeaky clean. The life of Mary’s grandson, James VI, the first officially freemasonic king of both Scotland and England, would be threatened by a plot hatched by “witches” on Halloween, 1590. The celebrated but trumped-up case of the “North Berwick Witches” kick-started over a century of Scottish witch hunts, and proved that your average Presbyterian could be just as vindictive as your average Catholic when it came to fighting Satan’s minions. While an equilibrium had been established between the two great Christian powers, neither can yet lay claim to being the saintliest, and each still has that heavy cross of guilt to bear. Another perfect doublecross, perhaps?

But the Reformed Church would not be allowed to remain squeaky clean. The life of Mary’s grandson, James VI, the first officially freemasonic king of both Scotland and England, would be threatened by a plot hatched by “witches” on Halloween, 1590. The celebrated but trumped-up case of the “North Berwick Witches” kick-started over a century of Scottish witch hunts, and proved that your average Presbyterian could be just as vindictive as your average Catholic when it came to fighting Satan’s minions. While an equilibrium had been established between the two great Christian powers, neither can yet lay claim to being the saintliest, and each still has that heavy cross of guilt to bear. Another perfect doublecross, perhaps?

Interestingly, the U.S. branch of today’s Sovereign Military Order of the Temple of Jerusalem (SMOTJ) uses the same reverse-barred configuration as Rosslyn in its official insignia. Its blazer badge, “hand-stitched in gold bullion,” can be purchased through its website, and part of the purchase price will be donated to a worthy charitable cause in the order’s name.

In certain Heraldic tomes it is said that the double-barred cross with the shorter bar above the longer is known as the “Cross Patriarchal.” What if Rosslyn’s builder, as his own little joke, reversed the bars in order to hang a “Cross Matriarchal” in the chapel’s ceiling?

Mary of Guise would have enjoyed that joke, but would we?

Rosslyn’s founder certainly used some elegant math when he plotted the chapel’s ceiling, but it was not an exact fit. There are four architectural elements remaindered in the fourth course, and one in the fifth—a total of five. However, this “mistake” may have been perfectly planned.

I visited the Grand Lodge of Scotland’s museum during my last trip to Edinburgh, and was struck by an exhibit dated to the early 19th century. It shows the Masonic compass, square, and level, surrounded by a five-pointed star. The five points are described as “the five points of fellowship.” What is truly striking, however, is that the star is upside down.

In Manly P. Hall’s 1928 classic, The Secret Teachings of All Ages, Hall has much to say about the five-pointed star, or pentagram. He claims that the figure is “the time-honored symbol of the magical arts,” and that “by means of the pentagram within his own soul, man not only may master and govern all creatures inferior to himself, but may demand consideration at the hands of those superior to himself.” He further claims that the star with two points upward is called the “Goat of Mendes” because “the inverted star is the same shape as a goat’s head.” The goat, as I mention in my “Joan of Arc Revealed” article (AR #42), is a recurring Masonic symbol.

Hall’s most apocryphal description of the inverted pentagram is the last sentence of his chapter about it: “When the upright star turns and the upper point falls to the bottom, it signifies the fall of the Morning Star.”

This is a troublesome concept, indeed.

While we watch the movements of the heavenly bodies, we do not expect to see them fall. By observing when and where they appear to us, we fix our place among them—and have done so far longer than documented history credits us. But Hall’s “fall of the Morning Star” eerily echoes the many far-flung world myths that talk of a cataclysmic day the sky fell. If it again becomes an observable phenomenon it will be we, not it, who are in motion.

I doubt we’ll find it funny.