Originally published in Atlantis Rising #42 — November/December, 2003. The sky graphics were created using the Skychart III program, available at www.southernstars.com)

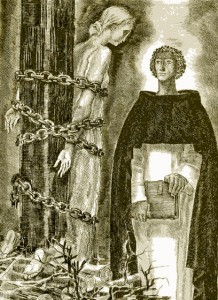

On May 30, 1431, a young girl was burned alive for heresy and witchcraft in Rouen, France.

On May 30, 1431, a young girl was burned alive for heresy and witchcraft in Rouen, France.

According to one account of the day, when she had succumbed to the flames the fire “was raked back, and her naked body shown to all the people, and all the secrets that could or should belong to a woman, to take away any doubts from people’s minds. When they had stared long enough at her dead body bound to the stake, the executioner got a big fire going again round her poor carcass, which was soon burned, both flesh and bone reduced to ashes.”

Although history tells us the victim was Joan of Arc, a simple shepherdess known then as Joan the Maid, the account of her execution shows even her gender was in doubt at the time—a doubt put to rest perhaps just a tad too neatly in the historical record.

Joan deserves a closer look.

Born on January 6, 1412, Joan is one of history’s best-documented figures—hardly surprising considering that the records of her several trials still survive.

At age 13, a “voice” told Joan she had been chosen by the “King of Heaven” to bring “reparation to the kingdom of France, and help and protection to King Charles.”

With much of France under English domination, French sovereignty was in dire straits. The forces of England’s Henry V had invaded in 1415, dealing the French a crushing defeat at Agincourt. When Henry died, in 1422, the English controlled all of France north of the Loire River, and in 1428 laid siege to France’s last stronghold in the region—Orléans.

Making matters worse, the French throne was itself in dispute.

King Henry had married the daughter of Charles VI of France, and under the terms of the 1420 Treaty of Troyes Henry’s son was named heir to the throne over the Dauphin Charles, son of the French king. Adding insult to injury, the tale was spread that Charles was illegitimate—a tale his own widowed mother, Isabeau, endorsed. Isabeau was enjoying the protection of the French Burgundians, allied to England, so what’s a mother to do? While the Burgundians held Paris, the Dauphin held a pitifully ineffectual court at Chinon.

Then, on March 4, 1429, Joan showed up.

She is granted an audience with the Dauphin on March 6 and, with divine help, recognizes him even though he is in disguise. She impresses him by privately relating a “secret” only he should know. She is then vetted by a court which recommends that Charles sets Joan at the head of his armies, and the rest is a history well-enough known to be covered only briefly here.

She raises the siege at Orléans and drives the English out. She then leads the Dauphin to his coronation as King Charles VII and, after a brief yet glorious military career, is captured by the Burgundians, sold to the English, tried and then burned at the stake while France’s new king looks the other way.

She raises the siege at Orléans and drives the English out. She then leads the Dauphin to his coronation as King Charles VII and, after a brief yet glorious military career, is captured by the Burgundians, sold to the English, tried and then burned at the stake while France’s new king looks the other way.

Twenty-four years later, Joan is tried again—posthumously—and in 1456 the original verdict is “nullified.” More than 500 years after her birth, Joan of Arc is canonized Saint Joan in 1920—cold comfort to Joan the Maid.

But the “sworn testimony” that paints the picture of Joan we are now expected to accept is a weird mix of the believable and the unbelievable, the commonplace and the miraculous. Although many swore to the testimony given, only a few privileged hands recorded it—so why must we believe what they have written? Perhaps instead of accepting what they wrote, we should look elsewhere.

In previous articles I have proposed the existence of a “secret brotherhood” with both the knowledge and clout to orchestrate certain historically pivotal events on earth, which simultaneously mirror the arrangement of the heavens, above. The articles suggest that these events are staged not only because out of the resulting smoke and thunder are born heroes and symbols guaranteed to weather the winds of time, but also because they are scripted to shape a nation’s sense of identity for centuries to come. Scotland has Robert the Bruce. America has the Star-Spangled Banner.

France has Joan of Arc.

One need only look at Joan’s entourage during her glory days, to see a troupe now recognized as players in the “underground stream of knowledge” game. Under the terms of the “Auld Alliance” between Scotland and France, many of her comrades were members of the Scots Guard, a group thought to have held strong ties to the Knights Templar, whose inner circle may have escaped from France to Scotland upon the order’s 1307 suppression for heresy, where they chose to quickly “disappear.” While today’s sizable Templar fan club subscribes to that theory, my own opinion is that the knights’ inner circle had taken the forward-thinking view that it was time to “rightsize” the corporation, and had done just that.

And then there is René d’Anjou, one of Joan’s companions on her trip to meet the Dauphin. One of René’s many titles was “King of Jerusalem.” Purely titular, the designation had nevertheless descended from Godfroi de Bouillon who, as the authors of “Holy Blood, Holy Grail” assert, had founded the shadowy Priory of Sion which, in turn, had founded the Knights Templar. René is known to have been a close friend of the young Leonardo da Vinci who, later in life, is thought to have been Grand Master of the Priory. “Many have made a trade of delusions and false miracles, deceiving the stupid multitude,” Leonardo wrote. He also held the highly heretical belief that Jesus was a twin! But more about twins, later.

One of the suspiciously precise details we know about Joan is her exact time of birth—one hour after sunset on January 6, a day variously known as the Feast of the Epiphany, the Day of the Three Kings, and the Twelfth Day of Christmas. Surprisingly, neither Joan’s mother nor any other witnesses at the “nullification” trial mentions that Joan’s birthday was an official holy day.

Considering the trial was meant to show that Joan’s mission had indeed been divinely inspired, I found that silence curious. And so I decided to consult a record I had discovered during my previous research—the arrangement of the heavens on the day in question.

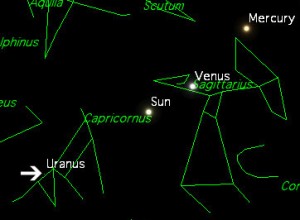

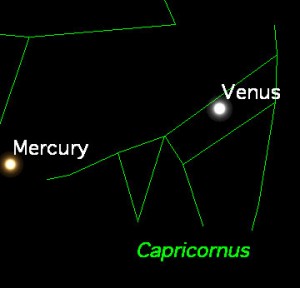

Shortly before dawn, the planet Mercury, Messenger of the Gods, rose above the bow of the constellation Sagittarius, the Archer, while Venus, the “morning star” and symbol of the goddess in many pre-Christian traditions, sat on the bicep of the arm that drew the bow. Then came the sun, hiding the heavens in the light of day.

Shortly before dawn, the planet Mercury, Messenger of the Gods, rose above the bow of the constellation Sagittarius, the Archer, while Venus, the “morning star” and symbol of the goddess in many pre-Christian traditions, sat on the bicep of the arm that drew the bow. Then came the sun, hiding the heavens in the light of day.

In Shakespeare’s “Henry VI,” written 179 years later, the Dauphin challenges Joan to a mock swordfight. Soundly trounced, Charles calls Joan the “bright star of Venus, fall’n down on the earth.”

Let’s now consider the name “Arc,” which in French means “bow,” and has also come to mean the leap electricity makes between unconnected points. It’s intriguing that on Joan’s birthday Venus drew the bow, perhaps to indicate that a woman had been chosen to let fly an arrow of hidden truth into the future, while Mercury, a.k.a. Hermes, would speed it on its way. And while the Dauphin’s reference to Joan as Venus fits this scenario neatly, a prophecy that had caught the imagination of the day fairly shivers with resonance. Attributed to Merlin, the prophecy foretold that a virgin riding Sagittarius would save France!

Uranus followed the sun on Joan’s birthday. Oldest of the gods, Uranus sat on the head of Capricorn, the Goat—a figure of enormous Templar significance. The accompanying illustration shows a winged creature with the head of a male goat on a human torso, with female breasts and a mid-forehead star. It is presenting a bright moon “above” and a dark moon “below,” a very telling Hermetic image “for those with eyes to see.” Considered by some to be Baphomet, the entity the Templars were accused of worshipping, it waits 18 years to appear again in the life of Joan.

Uranus followed the sun on Joan’s birthday. Oldest of the gods, Uranus sat on the head of Capricorn, the Goat—a figure of enormous Templar significance. The accompanying illustration shows a winged creature with the head of a male goat on a human torso, with female breasts and a mid-forehead star. It is presenting a bright moon “above” and a dark moon “below,” a very telling Hermetic image “for those with eyes to see.” Considered by some to be Baphomet, the entity the Templars were accused of worshipping, it waits 18 years to appear again in the life of Joan.

When Joan is received by the Dauphin, on March 6, Venus is riding the back of Capricorn, and in “Henry VI” a messenger brings news of Joan as “a holy prophetess new risen up.” In an initiatory rite of the Freemasons, a fraternity thought to have continued the legacy of the Templars, initiates are “raised” into the order from a symbolic death, and one of the persistent tales told about the rite is that initiates must also ride the back of a goat.

One freemasonic website has this to say:

“The Goat of Mendes or Baphomet whom the Templars were accused of worshipping is a goat-headed deity, being formed of both male and female principles, with a Caduceus of Mercury for its phallus. One arm points up and one down, with the Latin words ‘Solve’ and ‘Coagula’ written on them.”

“The Goat of Mendes or Baphomet whom the Templars were accused of worshipping is a goat-headed deity, being formed of both male and female principles, with a Caduceus of Mercury for its phallus. One arm points up and one down, with the Latin words ‘Solve’ and ‘Coagula’ written on them.”

The Latin words mean “dissolve” and “combine,” and might well describe the Templar business model upon the order’s dissolution.

But back to Joan’s nativity.

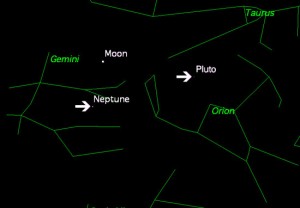

As the sun set in the west, the Orion constellation rose in the east. Since I have covered Orion’s significance in previous articles, I will not do so here—except to add that tiny and distant Pluto sat above Orion’s head like an invisible crown.

To Orion’s left the planet Neptune, God of the Oceans, separated the Gemini twins, and the Twelfth Day of Christmas became Twelfth Night—the night that Joan was born. One hour after sunset, weather permitting, Orion and Gemini would be shining brightly in the eastern sky.

Scholars have long argued the significance of Shakespeare’s title “Twelfth Night, or What You Will” since the play offers no explanation. It is the story of twins, male and female, who are separated by a storm at sea, each thinking the other has drowned. The woman masquerades as a man and, until the end of the play, there is much gender confusion, with a little cross-dressing thrown in for good measure.

Since the historical record conveniently tells us that Joan was born on Twelfth Night, it’s interesting that Neptune, named after the god of the oceans, separated the Gemini twins on the night of her birth, just as Shakespeare’s twins were separated by a storm at sea.

Methinks perchance the Bard’s mighty quill writ two tales—one hidden in the other!

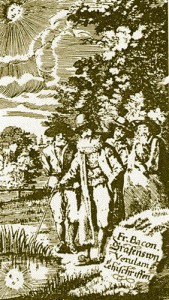

Next to the King James Bible, commissioned by Britain’s first officially freemasonic king, no books have enjoyed greater sales figures than William Shakespeare’s. And yet their authorship remains hotly debated. A top contender as the author/editor of both works is Francis Bacon, the English philosopher who lived contemporaneously. Thought to have played a key role in the birth of the Rosicrucians—an esoteric brotherhood with Templar and Freemasonic ties—Francis may have secretly worked to put in place a system whereby “lost” knowledge might eventually be rediscovered. He also shares resonant connections with the Goat and the Twins.

- As the Goat of Mendes draws our attention to a moon above and a moon below, the accompanying title page to Bacon’s “De Sapientia Veterum” shows Francis drawing attention to the reflection, below, of the sun, above.

- Bacon’s coat of arms shows two soldiers—likely Castor and Pollux, the Gemini twins. His motto, “mediocria firma,” has been interpreted as “the middle ground is safest.” In an age when heresy could get you burned alive at the stake, perhaps Francis was just protecting himself by not taking credit for saying too much too soon—preferring to let his rather milquetoast motto speak sterner stuff in times to come.

In the 572 years since Joan’s death, historians have been plagued by two pesky groups of revisionists—the “bastardizers” and the “survivalists.” The bastardizers claim that Joan was not a simple shepherdess, but was in fact the illegitimate daughter of Queen Isabeau and her brother-in-law, Louis of Orléans, making Joan the half-sister of the Dauphin and also, consequently, the aunt of Henry VI of England through the marriage of the Dauphin’s sister to Henry V. The survivalists claim that Joan escaped execution thanks to the secret efforts of Joan’s principal judge, Pierre Cauchon, and others in the English camp.

Within 25 years of Joan’s execution several brave souls claim to be Joan of Arc. It is interesting that one of these “imposters” was pardoned in 1457 by no less a personage than René d’Anjou, Joan’s companion-at-arms and titular King of Jerusalem.

It is highly unlikely that Joan was born on the day that history accepts—a day when the heavens were so oh-so-conveniently arranged. It is more probable that she was born earlier, and then delivered to foster parents on that astronomically auspicious day—for the record. It is also more probable that Joan of Arc’s miraculous career was orchestrated by the will of a cognoscenti that followed a mutually agreed-upon secret agenda from opposite sides of the battlefield—a brotherhood that counted the many thousands of ensuing war casualties as acceptable collateral damage—and which would continue to quietly promote a spirit of nationalistic and adversarial competition that would become very useful when the time came to divvy up and populate the New World soon to be “discovered” to the west.

The first cartographic appearance of the name “America” appears on Martin Waldseemüller’s 1507 map produced under the patronage of Duke René d’Anjou II, who had inherited the title King of Jerusalem from his grandfather. The map has recently been purchased by the US Library of Congress for $5 million, and will be the “crown jewel” of its map collection. Caveat Emptor!

Finally, while the positions of the six “ancient” planets on Joan’s “official” birthday could have been easily predicted at the time, the positions of the three “modern planets” should have been problematic. Uranus, conveniently on the head of the Goat, would not be discovered until 1781; Neptune, between the Twins, in 1850; and Pluto, above Orion’s head, in 1933. Hmm!

Perhaps they were simply allowed to be prudently re-discovered, when the time was right!

Francis Bacon wrote: “I begin to be weary of the sun. I have shaken hands with delight, and know all is vanity, and I think no man can live well once but he that could live twice. For my part I would not live over my hours past, or begin again the minutes of my days; not because I have not lived well, but for fear that I should live them worse. I envy no man that knows more than myself, but pity them that know less. Now, in the midst of all my endeavours there is but one thought that dejects me, that my acquired parts must perish with myself, nor can be legacied amongst my dearly beloved and honoured friends.”

Francis Bacon wrote: “I begin to be weary of the sun. I have shaken hands with delight, and know all is vanity, and I think no man can live well once but he that could live twice. For my part I would not live over my hours past, or begin again the minutes of my days; not because I have not lived well, but for fear that I should live them worse. I envy no man that knows more than myself, but pity them that know less. Now, in the midst of all my endeavours there is but one thought that dejects me, that my acquired parts must perish with myself, nor can be legacied amongst my dearly beloved and honoured friends.”

Although the girl whose body climbed the sky in a plume of smoke over Rouen on May 30, 1431, may never be known for who she truly was, she might someday be known for who she was not. Francis Bacon, in his way, made sure of it.

“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” Indeed!